By Erik Durneika

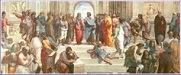

I believe that the roots of interdisciplinary studies go back to the times of the Ancient Greeks. Throughout the ages, the Greek people, within various city-states, have sought to form the perfect “Greek individual” – a person who showcases talents in many aspects (e.g. science, Liberal Arts, sport, etc.). The Greeks viewed excessive specialization in a field of study as unnecessary and as potentially harmful to the complex nature of human beings. Ancient Greek thinkers, such as Plato, were pioneers of transcending various disciplines and synthesizing certain subjects. The aforementioned philosopher deeply believed that a ruler of a defined area ought to be strong-willed as well as educated in various fields of study; therefore, the perfect “philosopher- king” ought to rule over the specific Greek city-state (Mitchell 358). On the other hand, Aristotle, Plato’s noteworthy student, highly revered drama and the arts in relation to humans in society. In other words, Aristotle thought that Greek citizens could relive and learn from mistakes by actively watching Greek dramas. A sense of catharsis would be invoked on the drama’s viewers and a purging of negative emotions and/or habits could possibly occur (Mitchell 307). After the Medieval era, this previously mentioned sense of acquiring knowledge is revisited in the Renaissance historical period.

Thus, the ideology of the “perfect human” was preserved even during the “dark ages” of the historical timeline.

Later on in time, Hypatia – who was a nonconformist philosopher – melded science with philosophy by teaching from various letters that were composed by her students. At her school that was located in the “City of Knowledge,” Alexandria (in modern- day Egypt), she also promoted tolerance of religion within the broad umbrella of science (Mitchell 90). Synesius later came under Hypatia’s spell and was motivated to integrate traditional Christianity with Ancient Pagan traditions (Mitchell 90). Interdisciplinarity, as seen in the two previously mentioned examples, created a chain reaction that encouraged individuals to cultivate a “creative Self” and to prove that nonconformity can lead up to historical “breakthroughs.”

On practically the other side of the world, East Asian artists – especially the Chinese – integrated philosophy, literature, and art into their pieces of artwork. Ma Yuan exhibited traditional Chinese literati traditions through his artwork. In his composition On a Mountain Path in Spring, Ma Yuan places a lone figure in a barren landscape – Daoist reverence for nature (Kleiner 66). The painting has a restricted palette and also features a figure that is dwarfed by the colossal landscape. The real motive of Chinese literati painters was to capture the essence of nature, further emphasizing following the “Dao,” or path, and acting in a mode of wu-wei, also known as non- action. In the upper right hand corner, the following poem of Emperor Ningzong is recorded using traditionally Chinese calligraphy techniques: “Brushed by his sleeves, wild flowers dance in the wind; fleeing from him, hidden birds cut short their songs” (Kleiner 66). This aforementioned poem is simple but incredibly elegant, which exhibits the Asian mentality of simplistic beauty.

Works Cited

Kleiner, Fred S. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: Non-Western Perspectives.

13th ed. Boston: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning, 2010. Print.

Mitchell, Helen Buss. Roots of Wisdom: A Tapestry of Philosophical

Traditions. 6th ed. Boston: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning, 2011. Print.

Cover Image: Erik Durneika