by Christopher Hizer

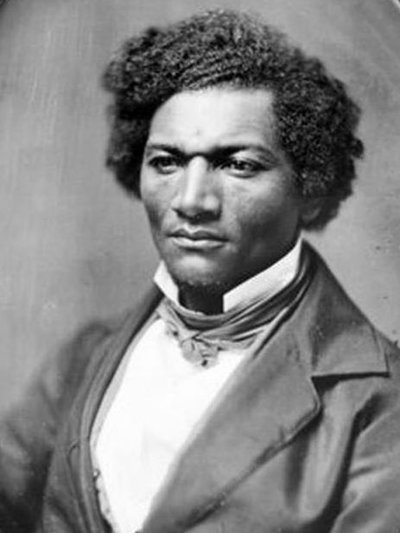

The inspiring Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an amazing, first hand account of slavery. With great wit and courage, Douglass walks us through the experiences of his youth, such as sleeping in an empty corn bag on a damp clay floor (Douglas, 34). We travel the gamut of emotion with Douglass as he fights the “slave breaker,” Mr. Covey, eventually finding his manhood (Douglass, 67). Perhaps most importantly, near the narrative’s end, he discusses his beginnings in the anti-slavery movement. By reading the “Liberator,” Douglass leapt forward in his journey for abolish slavery (Douglass, 100). His iconic status in American History began with his difficult education. Literacy and education, which allowed Douglass to obtain his own freedom as well as contribute to the abolition of slavery, were the most valuable possessions of the slave.

Douglass’ first experience with education was an eye opening one. It brought him to the realization that “education and slavery were incompatible with each other” (Douglass, 42). His mistress, Sophia Auld, who had been teaching him to read, was instructed by her husband to stop. Her husband, no doubt, knew the dangers of educated slaves. Mr. Auld stated education made a slave unable to work, giving rise to questions about his masters orders or possibly forged papers for escape (C. King). Coretta King wrote that with Mr. Auld’s objection, Douglass recognized reading and writing was the path to freedom. This realization lit a fire in Douglass. He learned any way he could, even trading bread to other children for lessons (Douglass, 43). The fears of Mr. Auld and hopes of Douglass outline the exact reasons literacy was so valuable to a slave. Education seeded a discontentment in the young Douglass. He began to hate slavery with his entire being. To the slave owner, being educated represented belonging to humanity. A slave who could question his master would become human and a human cannot be property.

Religion was also closely monitored by the masters as it might make slaves defiant. Slave children were taught to keep quiet about knowledge as a means of survival (W. King, 67). Douglass was taught a few Sunday school lessons around 1832 by a young white man, Mr. Wilson (Douglass, 55). This was ended by several religious leaders of the community. Douglass comically writes “Thus ended our little Sabbath school in the pious town of St. Michael’s” (Douglas, 56). Ever witty, Douglass again states the value of education, even in a religious context, in a religious town. Later in the Narrative, Douglass gives a different account of the Sabbath school. He admits that he was teaching other slaves or as he put it “learning to read the will of God” (Douglass, 74). He clarifies the intentions of the religious leaders. They would rather see slaves playing sports or drinking rather than behaving like thinking human beings. This hints that the masters feared not only literacy as a tool for escape but a motivator as well. A dumb and distracted slave would be easier to control. In a well used quotation, Douglass states “Saith the Lord: Shall not my soul be avenged on such a nation as this?” (Douglass, 104). This quotation states that religion should not align with slavery, yet the masters made it so. An educated slave, who could read, would certainly recognize this falsehood. The hypocrisy of southern culture in relation to religion and slavery was not lost on the literate Douglass (as well as others). Though he despised hypocrisy, Douglass was firm in his own Christian beliefs and was well educated in them (Thompson, Conyers, Dawson 35).

Critics of Douglass’ writings call to attention his use of “master’s language.” His style of writing is more like a white slave holders than a black slaves (Burns). Friends worried about his public speaking image and advised him to “keep a little of the plantation speech” for “it is not best that you seem too learned” (C. King). This criticism is still deployed today if one speaks in a learned or sophisticated way in certain contexts. Douglass’ books and speeches are amazingly well written, even for someone with substantial education. Despite critics, without such ability he may not have been taken as seriously as a writer. The entirety of Chapter 10 is written so powerfully that it would make an abolitionist out of anyone with a heart. Douglass’ description of Mr. Covey, rendered with both hate and a small bit of admiration, creates an antagonist worthy of the greatest hero (Douglas, 58-69). Maybe the most important use of Douglass’ education was to write the permissions ensuring safe passage to Baltimore during his escape (Douglas, 78). Forging his master’s writing cannot be insulted by calling it “master’s language.” The writing would have to have been in official language. It is difficult to fathom the dedication required by an individual with no formal education and such oppressive circumstances to write and speak as eloquently as Frederick Douglass. Perhaps if we did not take education for granted today, we would value it enough to learn as much. Throughout the Narrative, his astute mastery of language helped Douglass create an image of a boy, in a hopeless situation, who rose up to become a man that inspired millions.

Douglass led an amazing and influential life due, in no short part, to his education. It was not a formal education but the strong desire to learn that brought him lessons throughout life. Learning where he could and when he could challenged Douglass to work unbelievably hard. Douglass understood, at a very young age, that knowledge could see him to freedom. It is doubtful that as a child he could have foreseen the lasting impact of that knowledge, though. He employed the lessons and inspirations of religion to further his audience. He taught others to read in the name of religion and appealed to the Christian beliefs of slaveholders. Through his hard fought education, Frederick Douglass learned to master words and ideas that would win him a grateful audience 150 years later. Although nearly to a fault, his skillful use of the English language gave credibility to his writing and speech. No physical possession could ever equal the value of this man’s mind.

Works Cited

Burns, Mark K. “A Slave in Form but Not in Fact”: Subversive Humor and The Rhetoric Of Irony In Narrative Of The Life Of Frederick Douglass.” Studies in American Humor 3.12 (2005): 83-96. Literary Reference Center Plus. Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of The Life Of Frederick Douglass. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

King, Coretta Scott, and Sharman Apt Russell. “Frederick Douglass.” Frederick Douglass

(1-55546-580-3) (1988): 7-33. History Reference Center. Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

King, Wilma. Stolen Childhood: Slave Youth in Nineteenth-Century America. Bloomington:

Indiana University Press, 1997. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

Thompson, Julius Eric., Conyers, James L. and Dawson, Nancy J. The Frederick Douglass Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2010. Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

Image: Photograph of Frederick Douglass by Southworth & Hawes via the Onondaga Historical Association (OHA)