By Max Matheu

Identity loss and acquisition is a crucial aspect of the human condition. To define oneself through different cultural, religious, and social lenses remains a fixture of Western Civilization. In the contemporary period, the resurgence of tribalism and the creation of identity politics have both played roles in furthering identity beyond antiquated definitions of nationality or familial heritage. Edwin Arlington Robinson’s “The Mill” deals with issues of identity loss through the context of social, political, and technological revolutions that marked the turn of the 20th century. The permanent fixtures of a detached, industrialized society were just coming into fruition in the early 1900’s. The condition of the individual to develop through self-determination was considered a right. However, the extended reach of capitalism leads individual identity to become increasingly bound to labor. E.A. Robinson’s “The Mill” uses the fatalist dissolution of the economic identity of the mill worker as a critical analysis of materialism.

As the individual becomes more alienated from her labor and the means of production, self-identity becomes more entangled with representations of class. Social class stratification is measured by socioeconomic status, and materialism is a medium for self-identifying in relation to other members of society. However, economic identity plays a critical role in fully developing concepts of self. Natalya Antonoya defines economic identity as a “psychological phenomenon, reflecting the psychological attitudes of the individual to himself, as a subject of economic activity” (74). Economic relations further define the criteria for self, and the erosion of markets, the evolution of industrialization, and the collapse of industries become psychological factors in evaluating mental health. The repercussions of economic identity in conjunction with market collapse can be considered fatal. This is the cause for the double suicide in “The Mill.”

The anonymity of the miller and his wife is used to contextualize the critique of economic identity as it relates to materialism and lack of identity. The reader is only introduced to the characters of “The Mill” in their relation to the miller’s occupation. The wife is subjected to a dependent identity only existing as “the miller’s wife” (Robinson 1). Likewise, the miller is introduced in the context of his identity loss: “There are no millers any more” (Robinson 4). The two characters exist only as defined by an economic system. Moreover, the important factor in their collective identities is their relation to industry, or their relation to their labor. Without identity, an individual defined by an economic system can only be measured by the possession of material to supplement a loss of cultural capital or social class positioning. The appearance of a stable class positioning is more important to the economically defined individual than an actual identity. The miller is unable to provide an identity outside of his economic dependency on industry and Robinson sees this as the antithesis to humanity. In fact, it leads to the self-inflicted destruction of both the anonymous miller and his wife.

The collapse of the mill industry in New England due to migratory industrialization creates the context for Robinson’s poem. During American industrialization, the evolution of production from water mills to electric-powered factories displaced large amounts of workers and stagnated industry throughout the northeast as development was economically pressured to move to the New South (Koistinen 22). The movement of industry created a bleak scenario for the large number of workers whose identities were tied to the early stages of industrialization that spread across the mill towns of New England. The geographic demand for water as a source of power for the mills eventually became outsourced by the electric grid. As the mills and mill towns were outsourced, so were the identities of the workers attached to them.

The migration of industry is responsible for the death of the miller and his wife. The miller’s wife ruminates over her husband’s last words: “There are no miller’s anymore” (Robinson 4). This quote represents a double meaning for the death of the individual miller and the death of the mill industry. The figurative death of the miller’s identity as it relates to economic activity is in part due to the reach of capitalism, and its ability to augment self-awareness and affect psychological behavior. The passage also represents the industrial migration and how the effects of economic relations define the individual. This reflection on the loss of identity due to the collapse of industry becomes the most critical element of the poem. It highlights Robinson’s critique on materialism through the disillusion of economic identity. In fact, “decreased economic activity [has] produced the same proportionate increases in suicide rates”, which relates to the miller’s choice to end his life (Hammermesh, Soss 97). Because the miller is conceptualizing his identity through the mill, he is unable to exist when the industry collapses.

Robinson deconstructs economic identity through morbid imagery to highlight the antithesis of materialism to the greater good. Robinson’s “poetry is characteristically inferential, oblique, and reflective mainly of negative aspects of experience,” and it is through this representation that “The Mill” becomes a critique of American society at the turn of the century (Dauner 421). Louise Dauner goes on by asserting that “There are, then, positive values to be found in his reactions to life and society, although they must be deduced; that is, the good society, the competent democracy, must be inferred from the anemic democracy which it is Robinson’s technique to exhibit in terms of its weaknesses, discrepancies, failures” (421). When the miller’s wife saw her husband hanging in the mill, the imagery of suicide is not simply used for visual horror; it is used to suggest that if the dissolution of economic identity is death, then there can be no morality in materialism. The evolution of industry is more entangled with identity, and the dissolution of that identity is seen as the destruction of humanity.

The anonymity of the miller and his wife not only draws critiques to economic identity, but it can also be applied to the theory of alienation that indoctrinates individuals into assessing their worth via the industry that defines their communities (Bell and York 113). The structural aspects of a community can make it nearly impossible for individuals to associate their identity outside of the industry that provides their employment. The center of many mill towns were the mills themselves, and from there the process of alienation becomes somewhat distorted. In being confined to the labor, they are brought closer to the other individuals that create the community. These social networks are vital for the success of any member to be able to function properly within the constraints of their society, thus indoctrinating individuals to the belief that the industry defines who they are. The miller and his wife are intangible, yet the community that defines them is a reality.

Robinson goes on to define the past as diametrically opposed to the removed identity that labor alienation creates. The miller’s wife is introduced in terms of gendered labor through the scenes of domesticity. This highlights her identity as being strictly relative to the gendered labor she performs. However, even this is defined through the past by the inclusion of “was cold…was dead.” Her equative gendered labor identity no longer exists either (Robinson 2). The correlation between identity and labor is further affirmed when she goes to search for her husband at the mill: a physical representation of his identity. In knowing “that she was there at last” she confirms the dissolution of his humanity through economic identity in the past tense (Robinson 10). The reference to “a warm/ And mealy fragrance of the past” incites the remembered experience of identity that was not defined through economic relations (Robinson 12). In finding her husband dead in the mill, she finds the identity of the miller long gone; only to be supplemented by the omnipresent economic identity that faded as the industry collapsed.

A close reading of verb tense throughout “The Mill” comments on the materialistic nature of economic identity. Glorianna Locklear defines “Robinson’s subtle handling of verb tenses, sentence structure, and punctuation” as highlights of his ambiguous literary style which allows for a more thorough reading of his work (176). The ambiguity of past perfect tense in the first line of the poem “The miller’s wife had waited long” and subsequent use of the tense throughout draws a contrasting argument between objectively defined identity and the ambiguous nature of self-awareness through materialism (Robinson 1). It also represents a transition from a reflective past in the case of past perfect; an association between a reflective perspective on the identity of the miller and how long his wife had waited for her husband to return literally and figuratively. The passage of time from past perfect to past tense, from a reflective thought to an event that happened, can be clearly defined as the process of economic identification and its usurping of the individual through the conditioning of capitalism. Robinson continues to create the identity of the miller’s wife in reference to the material aspects of status: “The tea was cold, the fire was dead” (2). The symbolic status of the tea and the fire, as a demarcation of wealth or economic identity, being expunged, establishes the effervescent nature of materialism. Identity is relative to economic trends, and materialism is the embodiment of status symbolism; the collapse of the economic identity is inevitable.

The miller’s wife is aware of her own dependent identity to her husband and their collective economic identity. When the wife finds her husband hanging in the mill she is subjected to the fatality of dependency upon her husband. She is defined through him in the patriarchal aspect, and as well as through an economic dependency; in being “the miller’s wife,” she has no identity outside of his (Robinson 1). However, in her realization that “what else there was would only seem/ To say again what he had meant,” the cognitive process of the miller’s wife is displayed (Robinson14, 15). She already knows the miller is dead, but she has gone in search of his identity to define herself. The line “would not have heeded where she went” suggests that the miller’s wife is already set to end her own life to either escape the life of a widow or to protest her dependent identity on her husband and the industry in question (Robinson16).

The method of suicide by drowning is a representation of the gender disparity that highlights the identity of the wife. In deciding to take her life in the “one way of the few there were / [that] would hide her and would leave no mark, the antiquated gender role of institutionalized domesticity and adherence to the patriarchal dominance is edified (Robinson 19, 20). The inclusion of “leav[ing] no mark” shows the importance that domesticity played in cultivating identity for women at the turn of the 20th century (Robinson 19). However, what is most concerning is the desire to dismiss her own identity even in death. This comments on the nature of gender roles not only in terms of dependency, but also in the industrial context. The wife takes her own life in the “black water, smooth above the weir” that is a power source for the mill (Robinson 21). She willingly submits to the patriarchal and capitalist power of the mill. In returning her identity to the mill’s power source, the cyclical nature of identity loss and industrialization continues. Robinson has equated the awareness to economic identity as a symbol of death that creates the dissolution of the community, individual identities of the wife and miller, and the market collapse as merely costs of production, or fluctuations in market value.

Robinson’s strict usage of conventional poetic methods conveys new meanings towards the critique of materialism. Robert Frost in “Introduction to King Jasper” posits that Robinson used conventional writing techniques to find new sources of experimentalism in poetry (117). Frost cites that “Robinson could make lyric talk like drama” insisting upon the importance that Robinson crafted his poetry through conventional techniques of rhyme and meter to convey new meanings (Frost 117). The meaning of Robinson’s work in “The Mill” is related to the industrialization of identity that is dependent upon capital and investors (Frost 117). To Robinson, addressing the escaping individual in the shadow of economic identity was an approach that needed to be protected and idealized through conventional means to allow for an anti-materialist critique of the industrialization of markets and the individual. The conglomeration of social institutions as methods of indoctrination to devalue the individual could not be met with experimental verse, deconstructed punctuation, or lack of rhyme schemes. Robinson demanded the persistence of the medium to convey reason and moderation to quell the void materialism created in identity.

Robinson’s “The Mill” correlatively analyzes materialism and economic identity with the death and identity loss of the miller and his wife. He goes on to insinuate that the death of the collective human experience is the only outcome of a growing desire for material goods to establish identity. The cohabitation of industry and the individual is an illusion. Much in the same way that the ideology of ethical capitalism, equality in the criminal justice system, or the paradigm of meritocracy are fabricated to elucidate a platform for the continuation of inequality. The striking comparative analysis of early 20th century industrialization and its context in the 21st century remains as an edifice to the protraction of social, racial, economic, and political conflict that has defined Western society since its conception. The demand for a defined identity aside from corporate or market associations remains integral to individualism and self-determination. Moreover, it is defiance to the established hierarchical society that allows for the inherent truth of humanity to be conceptualized.

Works Cited

Antonova, Natalya. “Economic Identity and Professional Self-Determination”. Athens Journal of Social Sciences, vol. 1, no.1, 2014, 71-81.

Bell, Shannon Elizabeth and York, Richard. “Community Economic Identity: The Coal Industry and Ideology Construction in West Virginia”. Rural Sociology, vol. 75, no. 1, 2010, pp. 111-143.

Dauner, Louise. “Vox Clamantis Edwin Arlington Robinson as a Critic of American Democracy”. The New England Quarterly, vol. 14, no. 3, 1942, pp401-426.

Frost, Robert. “Introduction to King Jasper (1935)”. The Collected Prose of Robert Frost, edited by Mark Richardson, 1st ed., Cambridge, Mass., Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009, pp. 116-122

Hamermesh, Daniel S., Soss, Neal M. “An Economic Theory of Suicide”. Journal of Political Economy, vol.82, no.1, 1974, pp 83-98.

Koistinen, David. Confronting Decline: The Political Economy of Deindustrialization in Twentieth-Century New England. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2013.

Locklear, Glorianna. “Robinson’s the Mill”. The Explicator, vol.51, no. 3, 1993, 175-179

Robinson, Edwin Arlington. “The Mill”. Making Literature Matter: An Anthology for Readers and Writers, edited by John Schlib and John Clifford, 6th ed., Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2015, pp. 139-40.

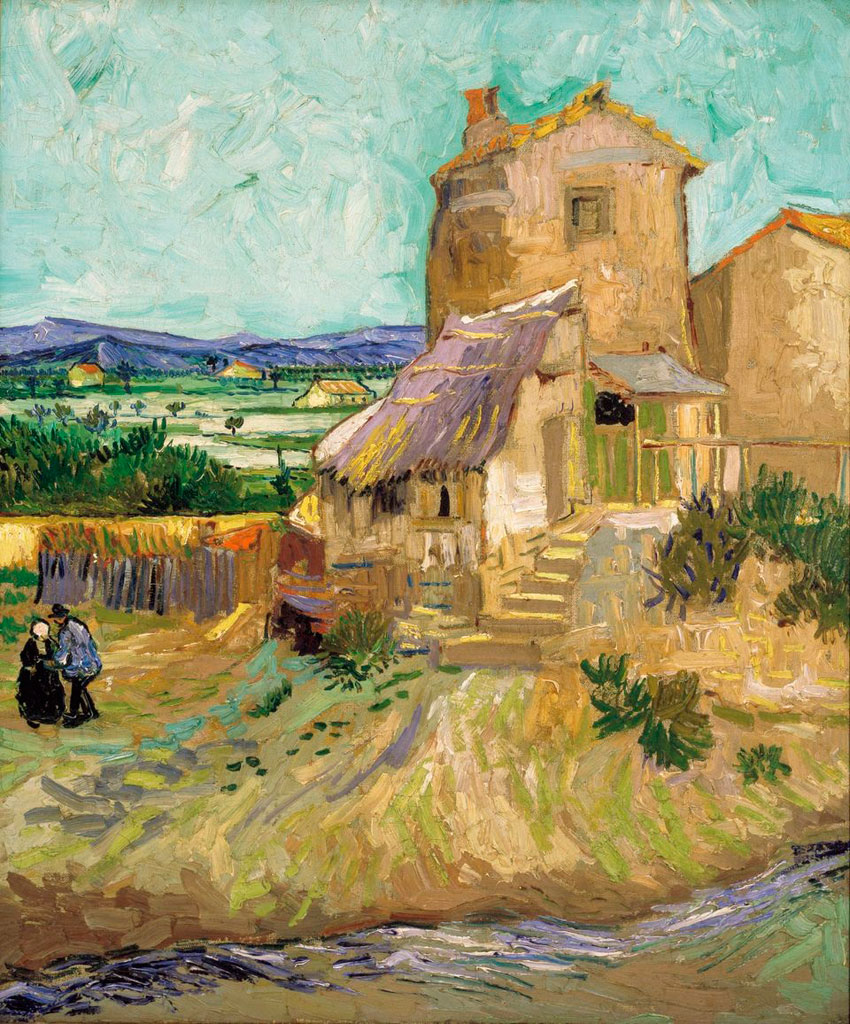

Image: The Old Mill (1888) by Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) via the Wikimedia Commons