by Brian Fermin

The Harlem Renaissance can be attributed to the “desire of African Americans to produce a distinctive black American culture within the larger national culture” (Mays 1031). The poetry of the Harlem Renaissance reflected the disenfranchised American Experience for black Americans; the works also helped shape the experience into a more equitable one.

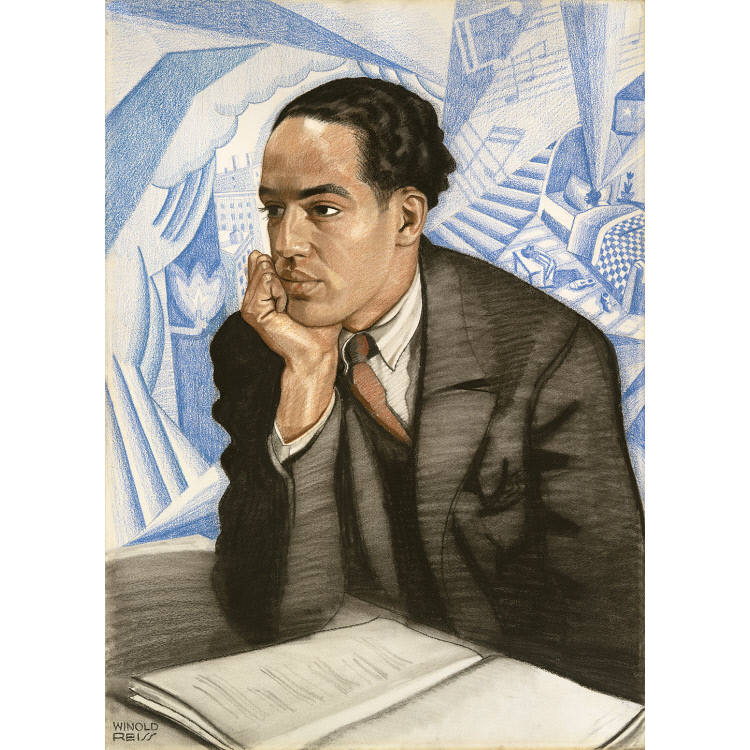

In Langston Hughes’ poem “Harlem,” optimistic word choice, a suspenseful mood, and repulsive imagery are used to convey how many black Americans felt hindered in the pursuit of their own dreams. The first line of this poem questions “What happens to a dream deferred?,” the dream that Hughes is referring to is the dream that any American hopes to achieve, a decent life with equal opportunity. The use of the word deferred is very deft, it points to Hughes’ optimistic look that this dream is still attainable and will one day come to his community. Lines 2 through 10 of this poem quickly throw many alternative options to the reader in the form of questions in order to set a suspenseful mood. The tension set while reading this section is reflective of tensions in America during the Harlem Renaissance. The brigade of questions set up the final line “Or does it explode?” This line relieves the tension with a more awe-inspiring and reflective alternative to the question. This final line is a call to action; “exploding” in this context isn’t inherently violent, it can represent an explosion of activism and pursuit of this dream. Throughout the poem, Hughes uses negative imagery to demonstrate the feelings of the many disenfranchised people in the nation at the time. The repulsive imagery: “dry up,” “fester,” “sore,” “stink,” “crust,” “rotten meat,” “sags,” and “heavy load,” (2-10) express the contempt that Hughes and his contemporaries felt for having their dreams deferred for so long. Hughes uses the literary devices of hopeful word choice, suspenseful mood and unpleasant imagery to reflect the unequal American experience of the Harlem renaissance and to paint the future of a fair one.

Hughes’ famous poem, “I, Too,” conveys the American themes of equality and perseverance through the use of symbolism and a confident tone:

I, Too

By Langston Hughes

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

Then.

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America (1-18)

The phrase, “Tomorrow, / I’ll sit at the table” (9-10) is symbolic of the equal opportunity that Hughes hopes for. Here, he is simply asking that black Americans may also have a seat at the symbolic table that represents America. Lines 5 through 7 of the poem set a very nonchalant mood, here Hughes is laughing off his misfortune and keeping his chin up in the face of adversity. This calm demeanor reflects the similarly optimistic view present in “Harlem,” where Hughes sees better days for his community. This confident tone carries over in lines 15 to 18 with the use of prospective language to boast about how America will one day appreciate his beauty, which can extend beyond appearances and represent everything that he has to offer as an individual. Hughes is sending out the message of perseverance in this section. Hughes is confident in the worth that he and his contemporaries have to offer and would rather let that worth show for itself than call for violence. “I, Too” uses symbolism to reflect the desire of equality and a confident tone to shape the dialogue in the nation towards achieving that goal.

Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die” takes a drastically different approach towards reflecting the American Experience, the poem utilizes contrasting imagery to clearly express the writer’s disdain and a revolutionary tone as a call to action in lines 1-14. The qualities that McKay ascribes to the two groups in this poem, the oppressed and the oppressors, are contrasting. The oppressed, which McKay includes himself in, are the target audience of this poem so they are described with sympathy and as victims with language such as: “our precious blood,” “our accursed lot,” “brave,” “nobility,” and “honor.” The oppressors are shown no sympathy, they are described with dehumanizing language, specifically: “mad and hungry dogs,” “the monsters,” “foe,” and as a “murderous, cowardly pack.” This aggressive and divisive language reflect the frustration that McKay and others subject to violent oppression felt in these times. As history has repeatedly shown, sustained oppression frequently leads to revolts. McKay uses a revolutionary tone to speak to his contemporaries, “O kinsmen! We must meet the common foe!” He speaks as if death is just around the corner, “What though before us lies the open grave?” regardless of what they can do, so a violent revolution is the final option that can guarantee the repercussions that he seeks. Black Poets of the United States states that “If We Must Die transcends specifics of race and is widely prized as an inspiration to persecuted people throughout the world. Along with the will to resistance of black Americans that it expresses, it voices also the will of oppressed people of every age who, whatever their race and wherever their region, are fighting with their backs against the wall to win their freedom” (Wagner). “If We Must Die” is a powerful poem that reflects the issues of the Harlem Renaissance by focusing on the injustice in the nation at that time.

Equality and contention were central themes to poetry of the Harlem Renaissance; a prominent mood, whether optimistic or ominous, played a big role in expressing these ideas in the three poems. Literary devices were used to both reflect the feelings of black America at the time and to reveal aspirations for the future. Poetry of the Harlem Renaissance reflected the conflict, anger, energy and humanity of the American Experience at the time. These works also contributed towards producing a distinctive black American culture while simultaneously pushing towards equality through collaboration with white artists and an increased exposure of black artists.

Works Cited

Hughes, Langston. “Harlem”. The Norton Introduction to Literature, Kelly Mays, W. W. Norton & Company, 2016, page 1043.

Hughes, Langston. “I, Too”. The Norton Introduction to Literature, Kelly Mays, W. W. Norton & Company, 2016, page 1045.

Mays, Kelly J. The Norton Introduction to Literature. Cultural and Historical Contexts: The Harlem Renasissance. Short ed., 2016.

McKay, Claude. “If We Must Die”. The Norton Introduction to Literature, Kelly Mays, W. W. Norton & Company, 2016, page 1046.

Poetry Foundation. “An Introduction to the Harlem Renaissance: Tracing the Poetic Work of this Crucial Cultural and Artistic Movement,”

Poetry Foundation, 2017, retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/collections/145704/an-introduction-to-the-harlem-renaissance

Wagner, Jean. Black Poets of the United States: From Paul Laurence Dunbar to Langston Hughes, University of Illinois Press, 1973, pp. 197-257.

Image of Langston Hughes by Winold Reiss via the National Portrait Gallery Collection