by Kristin K. Newman

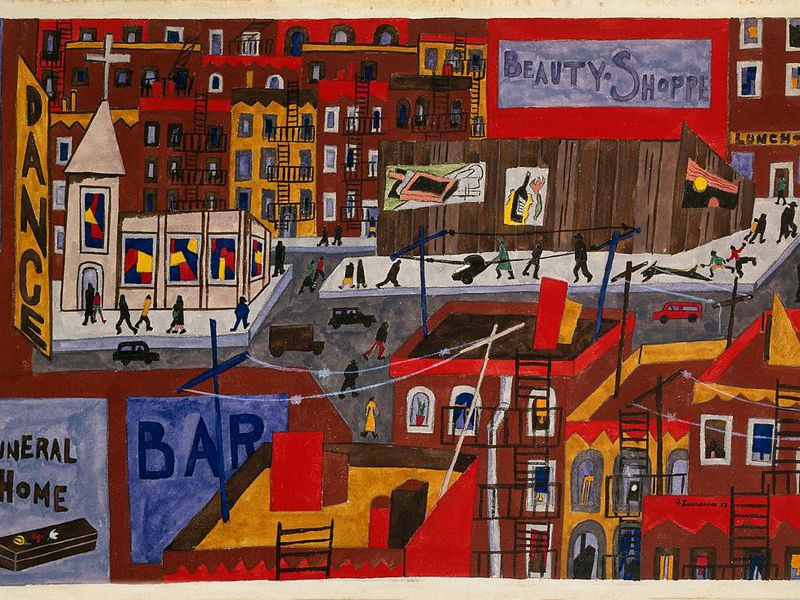

During the time period between World War I and the stock market crash of 1929, Americans in the northern section of this country witnessed an influx of immigration from the southern states, as more than 100,000 African-Americans chose to escape the social constraints of the Jim Crow south and settle in New York City (Mays, 2016). Life in the northern United States allowed black Americans the opportunity they needed to freely express themselves in the areas of jazz music, theater, art, and literature. An explosion of African-American culture burst into the consciousness of the American experience during the Harlem Renaissance, with a vibrancy, intensity, and soulfulness that was completely unknown to white America. This cultural richness was expressed in the writings of African-American poets, like Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, and Georgia Douglas Johnson, among others. This study will examine the ways in which the African-American Experience is reflected in the works of Jean Toomer, William Waring Cuney, and Fenton Johnson.

According to Cary D. Wintz, the Harlem Renaissance was a defining moment in American history for black Americans (Wintz, 2013). Wintz believes that the Harlem Renaissance was not defined by a geographical area in New York City, but represented a literary movement that affected American society across the nation on both cultural and intellectual levels. It expressed the black experience under the southern social and political constraints that pushed them to migrate to New York City in the north, where they could freely express their ancestry and African-American cultural heritage by using poetry.

The cultural impact of the Harlem Renaissance found its roots in the shared African-American experience of slavery. According to Lonnie Bunch, founding director of the National Museum of African-American History & Culture (Bunch, n.d.), the institution of slavery was like a blemish on America’s historical record. The African-Americans who migrated north could not simply erase their ancestral memories and the scars on their collective psyche. They would use these shared experiences to poetically reflect and comment on their unique culture. For example, the intensity expressed in Harvest Song (Poetry Foundation), by Jean Toomer remembers the harsh conditions of life as an enslaved field hand reaping the white man’s harvest while being subjected to fatigue, hunger, and thirst:

Harvest Song

I am a reaper whose muscles set at sun-down. All my oats are cradled.

But I am too chilled, and too fatigued to bind them. And I hunger.

I crack a grain between my teeth. I do not taste it.

I have been in the fields all day. My throat is dry. I hunger.

My eyes are caked with dust of oat-fields at harvest-time.

I am a blind man who stares across the hills, seeking stack’d fields

of other harvesters. (Toomer)

Toomer almost does not want to bring his memories to mind, remembering that chewing on a cracked grain from the field was a tasteless and inadequate way to satisfy the hunger of his people. He also knew well the pain of tired muscles, squinting eyes working in the blinding sun, and feeling the chill of night in his bones while he continued working after sunset, explaining a facet of African-American culture that would (perhaps) be unknown to white society in the north.

Another example of African-American soulfulness expressed during the Harlem Renaissance was a reminder in the poem Nineteen-twenty-nine (Poetry Foundation), by William Waring Cuney, who succinctly explained that it did not take the stock market crash of 1929 for him to understand the reality of hard times:

Nineteen-twenty-nine

Some folks hollered hard times

in nineteen-twenty-nine.

In nineteen-twenty-eight

say I was way behind.

Some folks hollered hard times

because hard times were new.

Hard times is all I ever had,

why should I lie to you?

Some folks hollered hard times.

What is it all about?

Things were bad for me when

those hard times started out. (Cuney)

Cuney hinted that some of the white American folks in New York City may have found the hard times of 1929 to be their first experience with hardship. He considered their fussing to be an over-reaction, because he could reflect on 1928, the year before the crash, and tell his readers that the hard times he experienced in 1929 were the same as those he had experienced in 1928. He did not have to lie to white society about the economic experiences of African-Americans; he would use his poetry to express the way things had always been for his people.

Other expressions from African-American poetry drew on their shared spirituality. Most enslaved Africans brought to the New World had practiced traditional African religions centered around ancestor worship and belief in spirits of nature and supernatural beings (Weisenfeld, 2015). According to Weisenfeld (2015), during the 1740’s a Baptist and Methodist evangelical atmosphere in the south set the stage for African Americans to accept Christianity. The conversion to Christianity for enslaved Africans hinged on an individual emotional experience. In a somewhat puzzling development, white southern society balked at the idea of their slaves becoming Christians. Many whites expressed reservations about blacks being exposed to their religions, because they did not want their slaves to learn the concepts of liberation and freedom, even in the spiritual sense. One southerner even expressed the thought that she could not accept the idea of seeing her slaves in heaven. From a religious and cultural standpoint, there was a great divide between black and white Americans. The migration of African-Americans to the northern United States allowed them to explore other cultural and religious options beyond their southern Protestant Christianity. Many black migrants became members of Holiness and Pentecostal churches, with their speaking in tongues, healings, baptism in the holy spirit, and prophetic interpretation. The evidence that this new African-American religious and cultural experience would come to be expressed in the Harlem Renaissance poetry is quite possibly found in the poem A Dream, by Fenton Johnson:

I HAD a dream last night, a wonderful dream.

I saw an angel riding in a chariot— (1-2)

In describing a supernatural dream or vision in this poem, Mr. Johnson provided a vivid description of a radiant angel in heavenly glory. His reaction to such an awesome sight leads us to consider the possibility that some influence from Holiness or Pentecostal teachings caused him to describe his physical reaction to this dream in the terms of a bowed head, as if in a trance, with his limbs trembling, much like the shaking and quivering that could occur during Pentecostal worship.

The literary importance of these three poems to the Harlem Renaissance is that they represent a culturally, socially, and religiously rich African-American perspective on their experiences in America. These 20th century African-American poets were skilled at expressing vibrant, intense, and soulful emotions that were mysterious to white American society. The lasting impact of the Harlem Renaissance poets on American culture and society is that they bequeathed a legacy of racial pride, racial identity, and racial equality for later generations of African-Americans (Wintz, 2015).

Works Cited

Bunch, Lonnie. Knowing the Past Opens the Door to the Future: The Continuing Importance of Black History Month. Retrieved from: www.nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/knowing-past-opens-door-future-continuing-importance-black-history-month

Mays, Kelly J. The Norton Introduction to Literature (shorter Twelfth Edition). W.W. Norton. 2016. Chapter 21. Retrieved from: digital.wwnorton.com/lit12shorter

Poetry Foundation. An Introduction to the Harlem Renaissance. Retrieved from: www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/53989/harvest-song

Weisenfeld, Judith. Religion in African American History. March 2015. Retrieved from: DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.24

Wintz, Cary D. The Harlem Renaissance: What Was It, and Why Does It Matter? February 2015. Retrieved from: www.humanitiestexas.org/news/articles/harlem-renaissance-what-was-it-and-why-does-it-matter

Image: This is Harlem (1943) by Jacob Lawrence via the Smithsonian Institution (Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden)